note: this week’s newsletter includes posts for all subscribers, and posts that can be accessed only by paid ($5 a month/$50 for a year) subscribers.

Bad news for 60+ brains. But don’t worry, you’ll soon forget it.

Scientists have long assumed that our brain function declines steadily from about age 20 onward. Since my 64th birthday was this week, that logic would mean I’ve suffered 44 years of slow brain decay. (There are acquaintances who would tell you it hasn’t been slow.) Yet I feel that my creative and cognitive thinking is better now than it has ever been. My brain is certainly less cluttered with negative feedback loops than at other times in my life. But what do I know? A new German study found that, contrary to accepted wisdom, the speed at which our brains process info remains pretty steady throughout our lives, at least until we turn 60, when it starts to decline. Oh well, I’m on the downward slope. Thankfully, I’m good at pretending to know things that I don’t.

She shattered the hype ceiling

Model Joani Johnson was discovered late in life. At 67, she is going strong.

A surprising look behind the eyelids

by Ellen Wexler

Ellen Wexler is a 70-year-old artist based in New York City and Southold, Long Island. She kindly shares a fascinating story of neurodiversity, below.

Close your eyes and picture a house.

What do you see?

Some people see a generic house form. Some see their own house or a friend’s house. Some are able see every house they have ever looked at.

Some people see nothing.

I’m one of them. I have what is called aphantasia, or the inability to visualize imagery from memory.

And now I ask everyone I know to close their eyes and "picture a house.” So far I’ve found at least three friends who see nothing behind closed eyes, including an artist who paints realistic portraits from photos.

Aphantasia is described as “a fascinating variation in human experience.” This condition, which is thought to affect 3 to 5 percent of the population, has only recently begun to be studied. The opposite condition is called “hyperphantasia.” It, too, affects a small percentage of people who can see images in the mind’s eye that are as vivid as real seeing.

The ability to visualize events and images plays an important part in people's lives. People think about a friend and can visualize their face. People with aphantasia are unable to visualize any image. Instead when we “imagine” we describe the object, explain the idea and remember facts. But see no images. Many of us find that not seeing images in our mind increases, rather than reduces, our connection to the physical world. Without a “mind’s eye” we have an increased eye for beauty, intense visual attention to the here and now, and an increased sensitivity to details of the world around us. It is reported that “aphantasia is compatible with high achievement.”

I am an artist who for twenty years has made drawings inspired by photographic images of moments I want to remember. I did not know that I had aphantasia until very recently, yet, unconsciously, my creative process developed to accommodate it.

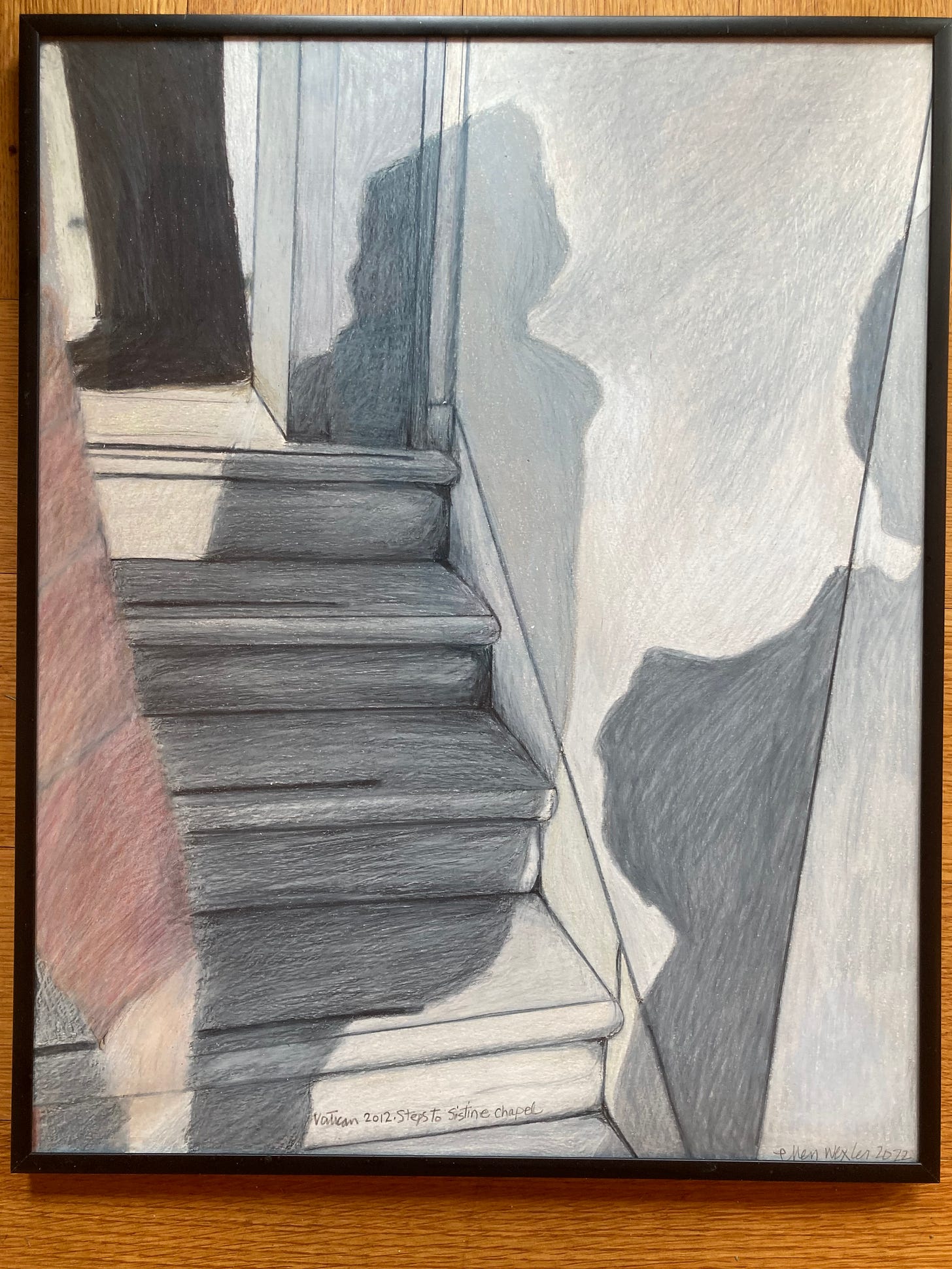

Stairway into the Sistine Chapel, drawing by Ellen Wexler

Most artists don’t begin with a visual image in their mind, but rather with a seed of an idea to see what develops during the making. Lacking a mental collection of images to retrieve motivated me to create memories through drawing. It begins with the desire to capture a memorable moment. With a camera I record the light, shadows, textures, objects — catching surprising compositions and interesting accidents. These photographs are intentionally incomplete and abstract, with odd angles and draped shadows. My drawings are images of those images. Like memories they are personal, illogical, not literal and so are difficult for others to decode. The drawings are my souvenirs and permanent recollections.

Jordan on Swing, 2020, photograph by Ellen Wexler

I only realized I had aphantasia a few months ago. That’s when my daughter asked me to close my eyes and tell her what I saw. She was startled to realized that I didn’t see anything, unlike her. Weird that after 70 years, this was the first time I’d realized that other people saw faces, trees and other images when they closed their eyes.

Last Supper at The American Academy In Rome 2005, drawing by Ellen Wexler

The University of Glasgow’s Centre for the Study of Perceptual Experience is researching aphantasia. You can join their on-line study and test yourself. Here are the details, from the Centre’s website:

Taking part in the study

“If you lack visual imagination, or experience an abundance of it, and would be interested in taking part in the Eye’s Mind’s research – and if you are happy for us to store your email address and responses – please complete this survey.

"The Eye’s Mind: a study of the neural basis of visual imagination and its role in culture" is a research project, which launched in January 2015, funded by an Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) Innovation Award. It is hosted by the University of Exeter and led by neurologist Adam Zeman who has a wide interest in the neural basis of experience, in collaboration with philosopher Fiona Macpherson (University of Glasgow), the neuroscientist Crawford Winlove (University of Exeter), the art historian John Onians, the artist Susan Aldworth, and postdoc Matthew MacKisack. The project unites researchers and disciplines normally isolated from one another in order to study our distinctively human ability to imagine, highlight links between our experience, brain science and art, and throw light on the wide variation in our capacity to ‘visualise’.

The following topics are for paid subscribers. If you’ve already subscribed, thank you! If not, please subscribe in order to see the full posts, below:

When older people say horrible stuff

Beware the VIBE SHIFT!

Pain can induce outsized hunger

Feeling weird? Mercury is in retrograde, always, these days

Hospice TikTok shows surprising depth

Now am I free to speak my mind?

Photo by Alexander Krivitskiy on Unsplash

We’ve all encountered older people who seem to have lost their “filter,” leading them to say the most horrendous stuff. That makes me wonder if filter breakdown happens as our brains age, or if these old people are just plain rude.

Our filters are what keep us from telling the boss that her car is ostentatious, and from telling a cop to go f himself