Enter the Curandera

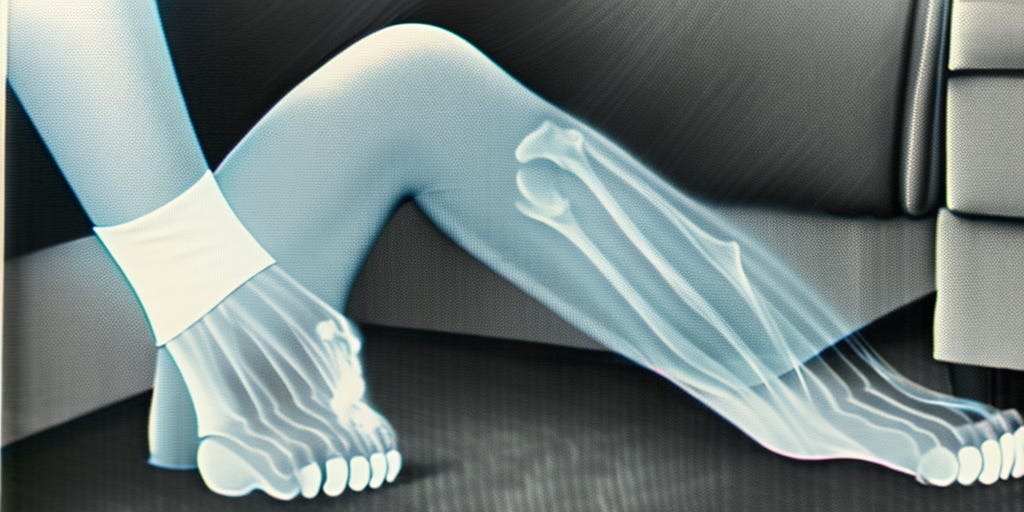

(No. 112) Sarah twists her ankle in a fall, requiring a post apocalyptic x-ray. Chapter Five from The Lost City of Desire

{I’m serializing my post dystopian novel here by posting one chapter a week. You can find the full archives here.}

I could see my aunt sweeping the sidewalk way up the block. She usually swept when she was nervous, and clearly that was the case now. I hated to upset her, but I also hated being around when she was upset. Her face twisted into a pretzel of fear, anger and relief when she saw me hobbling towards her, held up between the sibs.

“Oh my God! Sarah!” she cried out.

She hurried down the block to meet us.

“Where have you been?” she said. “I’ve been so freaked out.”

Her fearfulness irritated me. And that made me mad at myself – how could I be irritated with her? She was just worrying. That’s who she was.

I introduced Joe and Carmen and then sat on the nearest stoop to tell her the story.

“What on earth happened?”

“I fell off that ridiculous Schwarma and landed on the roof of a truck,” I said.

“What?”

“I’ll be ok. But I can’t put any weight on my ankle. And I’m dehydrated. And hungry. And tired. I couldn’t climb down, so I spent the night up there. Thank God these two happened by and rescued me. I'm sure I’d still be up there.”

“Thank you, thank you, thank you,” my aunt said, giving Joe and Carmen a hug.

“We were just walking by,” said Carmen.

“Oh my God, so lucky. You could have turned into a skeleton up there,” my aunt said. “Jesus! C’mon, let’s get you inside. When you didn’t come home we were afraid you’d run off.”

My aunt was always afraid she wasn’t good enough. That she hadn’t done enough for me. That she hadn’t been a good substitute for my own mother. And of course, no one could replace a mother, but she and my uncle had done the best they could. I loved them both, but they drove me nuts.

“I’d never run off without telling you,” I said.

But I knew, in fact, that I would.

I lay back on the sofa in the living room while auntie got us some sweet tea. With her, it was always the tea first, everything else later. She gave us each a cup and then had a good look at my ankle, which was swollen and bruised, with yellow and purple blotches and a red line radiating from the joint.

“This looks terrible,” she said. “Tell me if this hurts.”

She poked the swollen part and I gasped.

“Not good, not good at all.”

My uncle, who’d been napping upstairs, came in, his green eyes bright and sympathetic. He looked at my ankle and frowned.

“Not good,” he said. “Tara?”

“Yes, definitely,” my aunt said.

Tara was the healer we used whenever things took a turn for the worse, which, I’m glad to say, wasn’t often. I hadn’t seen her since the time a few years back when I’d had a leaky eye infection. For that, she took a dried mushroom out of a match box and and set it on the window sill and then blew the leftover dust from the matchbox into the corner of my eye. It stung like crazy but the next morning I woke up and there was no pus running down my cheek. I looked in the mirror, and it was clear.

My uncle ran off to get Tara, while Joe and Carmen and I drank tea and chatted to keep my mind off the pain.

“Where did you two come from?” my aunt asked.

“We’re from the boat from upstate, the grain boat that comes every year.”

“But I always buy from Joaquin.”

“That’s our father -- he passed.”

“Oh my goodness,” said my Aunt. “I’m so sorry to hear that.”

“He fell while hunting.”

“And your mother?”

“She’s with another man.”

My aunt shook her head in judgement. It was embarrassing.

“So you are left all alone. Just like this little one,” she said, patting my head. I shook her off and my ankle throbbed. I could feel it swelling. I winced as I reached for my tea.

“I’m sorry to upset you by talking about it, Sarah,” she said.

“Long ago,” I said. “And far away.”

I was drifting. I yawned.

I closed my eyes and glided on the pain into some kind of sleep.

I woke to Tara shaking my shoulders.

“Sarah, little Sarita,” she said in a singsong voice.

She had two vocal modes: deep and unnerving, the kind of low register voice that commanded you to pay attention; and high pitched and swirly, going up and down the register like a rollercoaster.

“What did you do to yourself, lady?” she said, her voice on the upward roll.

She wore a big muumuu almost the color of her skin. I could see dimples and stretch marks on her big calves as she bent close to my ankle.

“Problems here, girl,” she said. “I think it might be broken.”

Tara started giving orders: she needed a candle, a cup of rose petals, a shot glass of gin. She needed a blanket – “something you’d use on a picnic, so it can get dirty” – some cigarettes, some incense and a spoon.

My aunt and uncle immediately started searching.

“I’ve got some cigarettes,” I said.

My aunt looked surprised.

“Don’t worry. I just smoke them once in a while,” I said. “In that old Volvo down the street. I like to pretend I’m driving somewhere.”

My aunt blanched at my rebelliousness.

“Joe, can you grab them??” I said. “They’re in the dusty blue Volvo in front of number 389. Out the front door and to the right.”

Joe went out for the smokes.

“I’m going to do an x-ray of your ankle,” Tara said.

“What?”

“I’m going to look inside your ankle and see if it’s broken,” she said.

I had no idea what she was talking about, but that didn’t much matter, because I trusted Tara to do the right thing.

She told me to just lie back and relax, close my eyes and try to let the pain be itself, rather than fighting it.

“Soon, honey, we’ll get this figured out,” she said.

Tara was the most important healer we had. She’d cured infections, reset bones, and even delivered difficult babies, the ones who didn’t really want to come into this world. This being New York, she didn’t charge for what she did. Almost nobody did. Everything was done either for yourself --- like growing a garden or fixing up your home -- or as a labor of love. We’d give her food whenever we had it, but that was about it. We didn’t have much of anything else to offer.

Joe showed up pretty quickly with the cigarettes, and it only took my uncle about an hour to gather everything that he’d gone searching for. When it was all together, Tara told everyone to leave the room.

“We’ll let you sleep,” Carmen said.

“Yeah, we should get back to the boat,” Joe said. We’ll come by to check on you tomorrow. We’ll bring you some millet.”

Oh, so he is a charmer, I thought, my eyes closed in pain. I tried to rise up off the couch to see them out, but Tara gave me a long sideways look, laughed, and said, “Everybody but you!”

What was I thinking?

“Normally I’d have you stand, but since your ankle is killing you, I’ll have to sit down next to you.”

Everything hurt like hell, my entire body, but especially my ankle. It was a throbbing pain that seemed to fall from my kneecap straight down into my ankle joint, where it collected in a big fat lump of hurt. The pain was something other than me. I wanted to kill it.

Tara lit a bundle of incense that sent deep grey smoke into the room. She set the sticks on the fireplace mantel and removed two smooth stones from her giant black leather bag. One was a shiny green, the other was grey and rough, like she’d dug it up at a farm. I winced as she brought the stones to the edge of my foot, right below the swollen ankle. I was afraid they’d hurt.

“Don’t touch me, please,” I said.

“What was that, honey?” she said as she set the stones against my swollen skin.

I smiled, almost chuckling. She’d tricked me, but the cool surfaces soothed me.

She stood and reached her arms towards the ceiling and recited an incantation, eyes back in her head. I think it was Cuban, but I couldn’t say for sure. As she spoke her arms went up and down, and her feet moved back and forth in rhythm to her voice. The incense filled my senses and suddenly she dropped her hands to my face and said,

“Whooooooosh.”

She pulled them quickly away.

Then again, right down on my face.

“Whooooooosh.”

Again and again she did it and my mind got foggy and pretty soon I was in a trance. Within this trance I felt enveloped by gray matter, like I was inside an infinite tweed jacket, snuggled and warm and protected, and definitely fuzzy. Strangely easy – not comforting, but just easy. I had no sense of the outside world. No sense of anything other than a humming, buzzing noise and the feeling of being encased. And a figure at the edges, moving carefully, acknowledging me. I didn’t think about it at the time, only after I came to. I felt a rushing sound, like I was traveling to the furthest reaches. I rushed and rushed and then just disappeared.

Later, the light through the windows entered my eyes. I could see the sun had changed. Morning was now afternoon.

I felt rested. I felt safe. I felt warm.

Tara sat near me, calves crossed under her thighs.

“I did a deep dive,” she said.

“That’s the X-ray?” I asked.

“I took a good look at the inside of your ankle, and nothing is broken. But you sure messed it up! I worked with it, energetically, I put energy into it, took old energy out.

The huge throbbing pain had subsided, which was pretty awesome.

“You’re going to be fine,” she said. “Just perfectly fine. But it will happen again unless you make some connections, energetically.”

“What do you mean?”

“I mean that I see you are fragile in some ways and the reason is you’ve lost – or are losing – the connection to your mother.”

“Not much I can do about that,” I said.

“Oh yes, yes there is…there is much you can do. You just have to wish for it. Wish for that closeness, that bond. It can come in many ways, darling. I will help you.”

“Ha,” I said, not meaning to really laugh. More out of surprise.

“Oh don’t worry, you don’t have to do nothing now. This is a long-term project! Anyway, it’s more about the search than the resolution.”

I looked down at my ankle, which she’d wrapped with some kind of leaf.

“There’s a poultice under there,” she said. “Leave it on until morning, and then take a bath and go on with your day. It will have totally healed by the end of the week.”

“Thank you, Tara,” I said.

“Blessings to you,” she said.

She gathered her things into her satchel. Then she sat again and just looked into my eyes. With anyone else it would have been unnerving. But with Tara it felt just right.

“You must be careful on this journey you are planning,” she said.

Holy shit, I thought.

“Who told you I was planning something?”

“You told me – your essence told me.”

“Wow,” I said. “I’ll be careful.”

She handed me a piece of paper.

“Use this if you need any kind of help,” she said.

On the paper were the words:

La Gloriosa Frieda

The Heights of Mantchuken

“The Heights is a village near the wall,” Tara said. “And La Gloriosa is an old friend of mine. Don’t hesitate to ask for her help if you need it. And don’t ignore her advice if she offers it.”

She headed for the door.

“I won’t get up,” I said.

She laughed, a good belly laugh.

“Tomorrow you will,” she said, and closed the door. “And your ankle will be completely fine in just a couple of days.”

Cool, I thought. I will take Joe and Carmen on a hunting trip to Central Park as soon as I’m better. I wanted to show them around, to thank them for rescuing me.

Not long after Tara left, my aunt came in and sat too close to me on the couch. She had a pained look, the look she got when things weren’t going her way -- which, honestly, was a lot of the time.

“I heard what you said to Tara about going on a journey,” she said.

“What?”

“I know you want to find your mom, but that’s — you don’t know what you’d be getting yourself into,” my aunt said.

“Well, first of all, I didn’t bring that up — Tara said she “felt it” or whatever during the x-ray. And second, while I appreciate all you do for me, it’s not really up to you if I decide to take a journey. I’m 16 now. I can take care of myself.”

Uncle Jessie appeared, trying to look casual by leaning against the doorway.

“I agree completely,” said Uncle. “You know, Famous Ray says children are adults by the time they are twelve.”

Famous Ray -- Jeez. He was this preacher they’d been following for the last few years. It was getting worse. They’d fallen under this guy’s spell. He wore spangled jumpsuits, big octagonal sunglasses, and a floppy hat, shiny things to distract you from the junk he pushed. It seemed that everyone in this city was enthralled by spiritualists, charlatans and prevaricators. But Famous Ray was the worst.

“By the time they are twelve?” I said. “That sounds a little creepy.”

My uncle sat in his chair, looking wounded.

“He doesn’t mean it like that. Always twisting things around -- why do you do that.”

“Jessie, am I right?” my aunt said. “Sarah can’t go to the other side. It’s forbidden. God knows what could happen. Right? Am I right?”

“After all we’ve done for you, you want to go and worry your aunt like this?” said my uncle.

“Oh my God. This has nothing to do with you, or with her.”

“We made a promise to your parents that we’d take care of you if anything happened to them.”

“Which you’ve done,” I said. “And I’m forever grateful. But I still don’t know what happened to my mom and dad. They just up and left. I don’t even remember what they looked like.”

“If anything good had happened they would have come back for you,” my uncle said.

“Jessie!” my aunt admonished him.

“Well, look at the situation here -- we’ve been raising Sarah since she was five years old and I think we have a right to tell her what’s what. No use protecting her from the truth.”

“Which is?” I said.

“The truth is that you’re not leaving for the wall and that’s that -- finito!” my uncle shouted, and walked out in the backyard.

“Sarah,” my aunt said, coming over to give me a hug.

I wanted no part of it. I got off the couch and hobbled out the front door and down the street to my Volvo to have a smoke.

No fucking way was I staying in New York forever without first figuring out what, and who, was out there on the frontier, where the Hard Fork began.