For you: The Lost City of Desire, a novel about an unlikely utopia

(Chapters 1-7) In this story, New York in 2084 is a pleasant place, if you don't know any better. By Stephen P. Williams

I wrote and illustrated this novel with the idea that dystopia -- such as a devastating global viral outbreak -- can lead to utopias we have never imagined. I’m releasing one chapter every week, all of them archived below.

The Lost City of Desire

Chapter 1. Utopia Day

I opened my eyes to doves cooing on the fire escape.

Should I get up?

No, no rush. I’ll just stay in bed for a while.

I looked around my room, which was fancy like the wedding cakes I’d seen in ancient copies of Martha Stewart Living magazine. The white walls were frosting. The plaster molding was crunchy spun sugar. The floors inlaid with marzipan. I lived in a palace. The house was over 200 years old and all the little details from that distant past were intact. Still beautiful, despite all that had happened.

What had happened?

Since I was born – nothing. Nothing at all had happened. The sun came up. The sun went down. The world just was. I’d never known anything but a simple life.

I noticed a praying mantis on my windowsill. About eight inches long, it had green alien eyes, its front legs bent in prayer. Shiny, it belonged on a spaceship. These bugs always looked odd, but this one was especially unreal. It could have been made of plastic.

Then it occurred to me: was it a drone from the other side? Could the Westerners be watching me right now from across the river, beyond the wall? I’d never for sure seen a real drone, but everybody talked about them, how they took away our privacy, took away our power, what little we had.

Many times, my uncle Jessie said the Westerners were afraid of us, but for no good reason.

“What on earth could we do to them?” he said. “They’ve got their electricity, their little dronies, all their bio stuff. What do we have? Canned beans and a little peace and quiet, and floods. If we’re lucky, maybe a very nice tomato in July.”

They could secretly watch us, I knew, their cameras disguised as insects, birds, even leaves. It was fantastic to think about.

“Microbes is next,” my uncle railed. “Pretty soon they’ll send the cameras to live inside your body and control your genes.”

I felt a tickle up my spine.

“Have you ever met anyone from over there?” I asked.

My uncle scoffed. “Who would want anything to do with them?” he said. “They’re

paranoid. God knows why.”

As usual, I nodded in agreement while thinking my own contrary thoughts. This followed my aunt’s lead in how to deal with men, especially older men: “Just easier that way,” she’d told me perhaps 1,532,356 times (more or less). “Sometimes, when men get old, they get weird.”

“As if we’d want what they have over there,” my uncle said.

Well, actually, I thought, maybe we would want what they have -- movies and cars that actually drove, for instance. From what I’d read, that stuff wasn't that bad.

“I don’t know,” I said.

Auntie’s face tightened. I smiled involuntarily, out of discomfort.

“You’re laughing?” she said.

I shook my head no. But was I?

“Even if we did want what they have, there’s no way we could get it,” Uncle said. “They don’t want us over there. That’s why they built that wall. Who’s gonna go there? They throw you right in prison.”

The problem with buying into all this was that I’d never even seen a Westerner. Not one. Ever. Ipso facto, you know. So how could everyone be so certain?

The Westerners followed what they called the Hard Fork, some kind of religion that I didn’t really understand, other than that they had forked off from us decades before, and closed us down by building the wall. They’d been frightened by the disease, and they still saw us as carriers, even though I’d never been sick a day in my life. They also hated our religion -- well, actually, they hated our lack of it.

They were tough, so the story went. You didn’t want to mess with them. Everyone had plenty to say about them. Like, they were smart and devious. They had spider-drones that could actually weave webs that amplified their range – the bigger the web, the better the transmission signal. They’d climb your walls, make a web, film you and send the images back. That really got people mad -- the idea that The Westerners could watch us even in our bedrooms. Wherever there was light.

I didn't tell my uncle, but I thought drones were pretty cool, really -- exciting, if they actually existed. Something different for a change. I had nothing to hide.

I pulled my sheet up to cover my body from the mantis’ prying eyes. It remained passive on the windowsill.

If it was a camera drone disguised as an insect, it was doing a pretty good job of it.

It looked very praying mantissy, very real, staring into space, breathing in and out. Would a drone breathe? I took a breath myself.

I folded my hands over my heart and found my center. My mother had taught me this when I was just five or six years old. She said God lived in your center. And not that mean-spirited God the Westerners talk about, either. I’m talking about the good God. The loving God, the spirit God. The one that guides you well and protects you. You just have to find her.

I took another deep breath, felt better. I looked into the mantis’ odd, liquid eyes for a camera but saw only an alien. Nothing but eyes looking into another dimension.

I didn’t really understand cameras, cause I’d never used one, and I’d never seen a robot in action either, but I got the idea. This little guy looked like life to me, not like a machine. It was probably just waiting quietly for a meal to come within striking distance. It couldn’t be spying on me. What would the Westerners want to know about me anyway? They had no reason to send a drone for me -- I hardly even had a life. No life, that’s life, all life just strife. That’s what the guy who shoveled mud off the footbridge over the 14th Street River sang.

I had no school, no appointments, no friends my age. Everything I did for fun I had to invent. I even had to invent what “fun” meant. My aunt and uncle couldn’t explain it to me, so I read a book about it. Hopscotch, parties, balloon animals -- I didn’t recognize any of it. The amusement parks. The EDM concerts. Comedians. The prom. And one I really wanted to try: shooting cans. God I would love to have a gun. I never came across any guns in New York. Just to be able to hold one for once. So cool. All I knew about any of that stuff had come from books and my imagination. It was all in my head. I learned to let my imagination roll and see what comes out.

Like the game I’d play sometimes, where I’d wake up and name the day, make it special. Give it some meaning, a reason for being. Otherwise, you could get lost in the stillness, the sameness of each passing day. These special days gave me a purpose.

There’d been Happiness Day, where, duh! everything had to be happy. I’d picked flowers and put them in a vase for that day. Sprinkled glitter in my hair. Skipped instead of walked. Smiled at everyone I saw (which was about 3 people the whole day – not unusual). And felt happy all day. You couldn't do that every day, but once in a while, cool.

Today, I decided, will be Utopia Day in New York City. Classes are cancelled (I’d never been to a class, but I’d read about how great it was to cancel them). I decree that traffic is suspended the length of Broadway (there are no working cars anyway, so that was easy). All boutiques will give away free clothes (what hadn’t already been ransacked was there to pick, like mountain fruit).

This will be an amazing day, I thought. Utopia Day. What would you find in Utopia? I asked myself.

Steaks?

TV shows?

Private jets?

Sushi?

These were the foods in magazine photos.

Ok, I thought. If I narrow it down to stuff I can actually have, what would that be?

Food. Good food. Basically, that’s it. That’s really all it takes to make utopia in this world.

So, to make this day wonderful I’ll prepare something fresh and sweet and wonderful for lunch, I decided, like tomatoes and basil, or even fish if I can catch some at the river. Dying seemed normal -- the human bones were still all about. Yet killing fish or oysters troubled me. Still, I had to eat.

My father had taught me how to fish in the Hudson when I was almost too young to hold a pole, while my mom sat on the grass, reading a book. They were kind, as I recall, and full of love, and I missed them terribly. True utopia would mean being able to hang out on the couch with my parents reading books and drinking tea.

I pictured them suddenly opening the door to my room and coming to sit on my bed.

“Sorry we’ve been gone so long, Sarah,” my mother says.

“We shouldn't have just left you,” my father says.

I look around my room, all the emptiness there amid the beauty, and I’m hit with the quick sharp pain of knowing this will never happen. I’ll probably never see my parents. It’s just another day.

The praying mantis was gone. On the fire escape another dove fluttered its wings like shuffling cards. Out the window silence, save for the wind blowing down the city canyons.

I rolled out of bed, went down the shadowy hall to the bathroom and washed my face in the dim light. I felt someone lurking, a man. But there was no man, just the feeling. I was never sure what to do with this feeling. It was an often feeling. I felt like I had to do things a certain way, like this nonexistent guy was going to judge me. When I splashed my face, the water had to hit both eyelids at the same time.

The water felt cool and clean on my skin, a miracle gift from the smart smart water dudes who ran New York way back in the 1800s. Since the city reservoir was upstate at about 70 feet above sea level, and water always found its own level, nobody in any buildings lower than six stories ever needed to pump water into their tank. Whoever built that was a different breed. Pretty much nobody built anything these days. At least that’s how Terence put it. He had a reading room he called The Libray, where I spent a lot of time. For a basically illiterate guy he sure knew a lot.

I got dressed and walked down the dim stairway to the street, stepping quietly so as to avoid the attention of my aunt and uncle -- I didn’t want to talk, had no fears to share that might satisfy their need for fear and more fear, the world a crab bearing its orange claw down on your finger.

Everything was so quiet. I wanted action, though I didn’t even really know what that would be. The lack of change in my life was driving me a bit mad -- relentlessly closed.

I needed a smoke. I loved the floating silver stars in my vision and the melting brain feeling when I inhaled so deeply that life became the smoke. Marlboro. Salem. American Spirit. So many varieties tucked in all the empty drawers in all the empty apartments.

Don't tell nobody.

“Those things will kill you dead,” my aunt said. “Cancer sticks.”

Well, first, I had no idea what cancer was, and second, who cares, when they give you that feeling that you’re in a new world, for a moment at least?

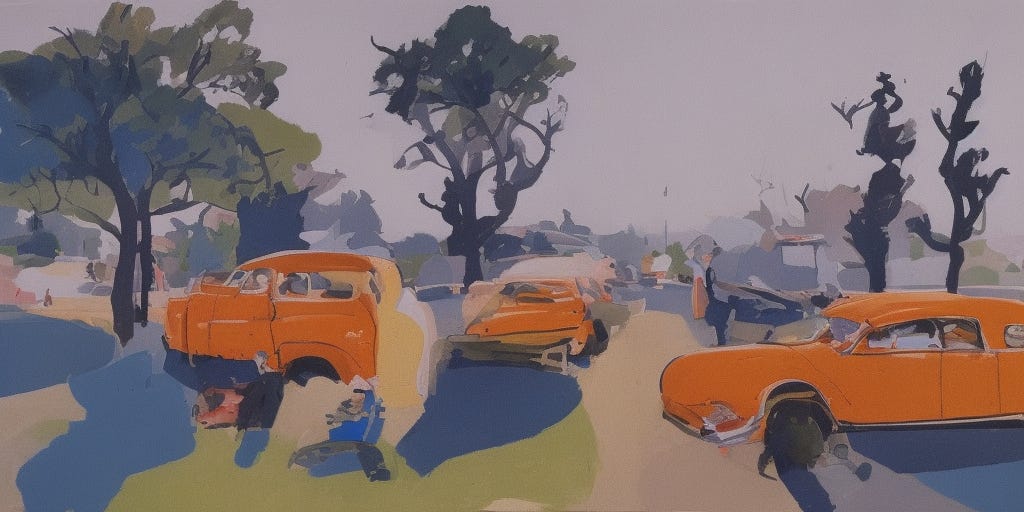

Out the front door and onto the street full of dead robot cars. Most were locked, dust-covered, streaked with pigeon stuff. Some had been broken into over the years and people used them for whatever they wanted. One up the street had crashed through the pavement, so it sat in quicksand about 8 feet down. Sooner or later the whole neighborhood would sink like this. The Hudson was seeping in this far now, and at super high tide could creep all the way to Ninth Avenue. I walked around the sinkhole and stopped at my favorite car, an old Volvo people mover I’d broken into earlier in the year. I opened the cabinet under the screen and pulled out the pack of cigarettes I kept there.

It wasn’t like I had to hide them from anyone. I just liked hiding them. I had amassed enough cigarettes to last a year, at least, scavenged from the basement of a deli over on 22nd street. A few dozen cartons of Marlboros. Stale for sure. Older than I was. But still, cigarettes!

I was 16. I could smoke if I wanted to. I’d been smoking since I was 12.

I lit one of the cigarettes using a match from my stash and coughed. Damn, I liked that feeling of coughing and smoking. What was it about that? Made me feel alive. I inhaled the poison smoke and pulled it further and further to the bottom of my lungs, into the tiniest air holes and the dizziness hit me, and the light exploded in my eyes and I felt momentarily sick and leaned my head back into the vehicle seat. Nice.

I kept the door open cause the windows didn’t work. I stuck the smoke in my mouth and imagined the car driving me here and there, me calling out, “Hudson River Parkway to Inwood, please,” and the car just taking off through the empty streets, battery charged, computer navigating the nonexistent traffic. I’d never seen a vehicle actually moving, not in real life. Only in my mind. So, as I drove nothing moved but my imagination. That was fun while it lasted – a good start to Utopia Day in New York City. And then, well, it wasn’t.

Chapter 2. The Fall

Morning, and I had vegetables to collect from the highline gardens – Uncle Jessie had asked for tomatoes and cucumbers, if I could get them, and maybe something else. For some reason, the rats liked the cucumbers once they got big -- you had to get them early, when they were small, and I thought now was about the right time for a cucumber harvest. Uncle Jessie was going to make beans today, and beans were pretty dull without some colorful things alongside.

A block from my house I passed the herb house. The Johnsons lived there, and every one of them – 14 kids and an ever-changing number of adults, were always high. Always. They raised weed on their roof top in the summer and smoked it through the winter. They’d shoot you with an arrow if you tried to steal it. If you tried to shoot back, they’d lock you in the basement for a while. Seriously.

I had smoked herb once, a year before, when I was 14, with a couple of the younger Johnsons. I got high, and for a few minutes it felt great! But then I crashed, just felt low, consumed with a feeling of abandonment, of worry. Unlike with cigarettes, which faded within a minute, the high from weed just dragged on and on. Didn't appeal to me at all. I didn’t need it.

Sure, I got anxious. Sure, I smoked cigarettes. Sure I liked to escape what I was feeling. But weed just took you down, sent you to bed, put you to sleep. I wanted good things. I wanted new things. I wanted a big change in my life. I wanted things to actually be different! Not just weed different.

Also, I just didn’t like the Johnson kids very much, weed or not. This was one of the few things I agreed with my Aunt and Uncle about. Those Johnson kids didn’t do much at all but lie around. This was too bad, cause there wasn’t anyone else to hang out with.

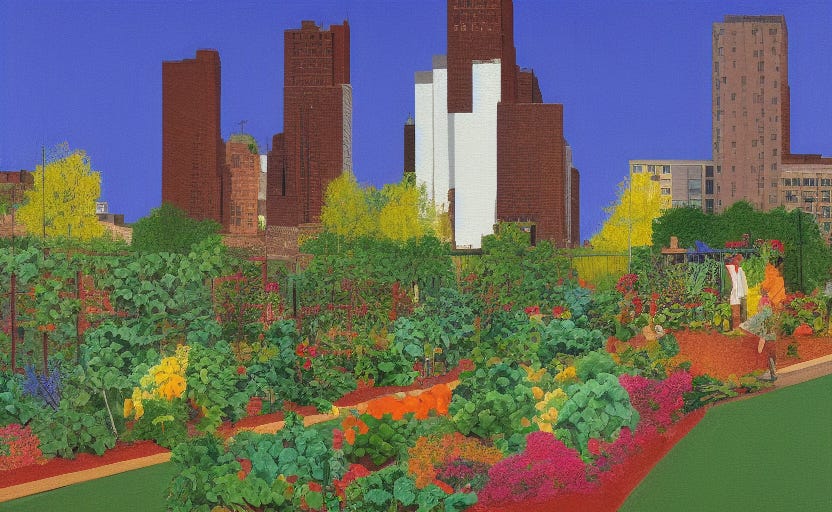

A block past the herb house I stepped onto the wooden walkway someone had built to carry you over the flood tide when it happened, and climbed the stairs to the highline. Trains used to run up and down the highline, back in the 20th century. Then it was turned into a park, and there were still signs up there describing sculptures and other art. One talked about a little garden area that had been annually sprinkled with carbon so it would turn into a desert. Overgrown now. When the moon was full and a storm was coming the water would get so high that you could climb up there and drop a line over the side for bluefish.

No one lived over here anymore – not much of anyone, at least, and those that tried never lasted through the big storms. But it was great for gardening. I liked the view. I liked the sun. I liked the whole thing. From up here I could see all the way across the Hudson to the battered Hoboken waterfront, and all the way up past the George Washington Bridge.

Something glinted on the water way up there. I saw a speck under the bridge. Could it be a boat? I wondered. We didn’t get too many of those.

But when I squinted to focus, it disappeared.

As I approached Old Thomas’s garden, I saw him sitting in a chair behind a wall of tomato vines. He’d taken a bite of a fat red one in his hand and was sprinkling salt on the tomato’s open wound for the next bite.

“Take as many as you like!” he called to me as I passed, and I said I would.

I passed the sweet-corn lady napping in a corner of her plot, sun on her face. She’d share her corn with anyone who was hungry.

I got to our plot. My aunt and uncle had planted carrots and cukes and a bunch of other stuff, and now there was so much to eat. This was nothing unusual, for sure. Everybody who remained in the city had a garden somewhere. It was just how we ate. I loved being up here, the river lapping below.

I pulled a carrot right out of the ground, brushed off the dirt and ate it, so crunchy and sweet. There were orange carrots and yellow carrots and blood red carrots, lots of them. I harvested a dozen and then stood up to check out the corn. Sun glinted off the river down below. I brushed my hands clean on my jeans and walked towards the raggedy skyscrapers at the end of the highline.

No one lived in these skyscrapers. The windows didn’t open. There was no air. As the years passed rainwater seeped in through the seams, and up from the deep basements that now were flooded, like the subways and everything else underground. Inside was a stew of mold and rot -- disgusting. The plaza was centered around a giant sculpture of intertwined stairways-to-nowhere. You could climb them whichever way you wanted, but you never really got anywhere except a little higher or lower. It seemed like it should be meaningful, though I never could find the meaning.

I called it the Shawarma after the faded signs selling carved meat on the side of a food truck that sat vacant and rusting at the base. It had the same shape. I climbed up the Shawarma’s endless staircases, stepping over the thick wisteria that nearly consumed it, to the top where I had an excellent view up the river. Sure enough, a sailing barge was coming our way, sails wide for a full run downstream.

Early every summer the barge arrived from upriver loaded with wheat, rye, barley, all kinds of grain. The captain was a guy named Joaquin. We’d trade the stuff we scavenged – saws, food grinders, Patagonia jackets – for what the farmers upstate grew, and Joaquin would take all our stuff back north to sell it. We’d binge on the new food for as long as it lasted, eating roti, porridge, levaine, rye bread. It was good. But what I remembered most was this boy. I didn’t know his name, but he'd come down on the barge with his father, Joaquin. I’d seen this boy from afar, and he’d seen me, too, I knew it, but both of us had been too shy to say howdy. He was sunburned and strong and had such a face. And now, it seemed, he was here again.

I recalled my uncle saying that Joaquin was way too hard on this boy. “He smacked him, I saw it,” my uncle said.

“Good lord,” said my aunt.

My heart hurt for a moment and for a second I thought I was sick. I wanted to protect that boy. I’d never felt this sensation before.

I kind of liked the feeling. Feeling his hurt was actually kind of sweet.

I climbed up and stood on the edge of one of the Shawarma’s copper colored railings, holding on to a thick vine so I could lean out for a better look up the river. I’d climbed up there a dozen times before to look at things. But this time the vine didn’t cooperate. It pulled away from the railing tendril by tendril and suddenly I was hanging in the air.

Oh my God.

Shit! I’m falling.

I hung onto the vine as it pulled bit by bit from the railings and dropped me onto a metal beam. I hit something sharp and fell till I hit this metal. I twisted my ankle. Damnit! I landed on something with a full body slam and that’s the last I remember. The world went dark.

I came to under the fading sun, my ankle throbbing, pain, pain, pain, a screaming pain. I was on the roof of the shawarma truck, about 15 feet off the ground. Damnit! But at least I hadn’t hit the concrete. I bent down to rub my ankle and it was swollen and black and blue. I untied my shoe and let my foot be free. A relief. I sat up and looked around.

I’m stuck.

I’m screwed.

No water, no food. The sound of water falling down the side of that skyscraper right behind me, God knows from what.

It hurts too much to move. Can’t climb down.

I’m just going to have to sit here until someone comes along who will help me.

Hah!

What’s the chance of that? Very small.

Night falls. Water falls. I don’t. I stay on top of the truck. I wish a drone would see me and save me. I wish a dozen little drones would clip on and carry me away to some place lovely and fresh.

To calm myself I think about an evening I spent at The Library with Terence a few months before. We talked about Emily Dickinson. Terence had always liked me to read her poems to him. This night, we sang them to each other like nursery rhymes. As I left, he handed me a thick manila envelope.

“Check this out when you get home,” he said. “Don’t show it to anybody, because they won’t understand. It’s all about the wall that separates us from the Westerners. How to get in and how to get out. I know you’ve been thinking about it.”

“How did you know?” I said.

“How else could it be?” he said. “You’re an orphan in search of meaning.”

Inside I felt excited and happy. I hugged him.

“You’re an amazing friend,” I said.

In my room I opened the envelope and pulled out a stapled folder with a sliced side view schematic of the wall. It was amazing. I’d always thought that the wall was a giant slab of concrete, thick and ugly, but the schematic showed it was hollow, its interior space filled with two tunnels and a series of rooms.

I imagined myself scaling the wall, blue skies above. Then I fell asleep on the truck roof, my ankle throbbing.

A dream: a boat in the river, rescued off an island. She’s free.

I woke up the next morning to the sound of someone kicking a glass bottle along the wooden walkway, below. The tide was out and the neighborhood was temporarily dry. The bottle clumped and banged along the walkway like a cavalry. I leaned over the edge to see what was up. It was him, from the boat, walking slowly with his sister.

Chapter 3. A hungry spring

Joe palmed a stone in case anyone tried to jump them — he’d heard plenty of stories about the city and didn’t want Carmen to get hurt. New Yorkers would as soon knife you as feed you, he figured. That’s why nobody ever came down from upstate. But he wasn’t too worried. He could handle it, for sure.

It’s not like everything was beautiful back home, anyway. It was ok. Yeah. But he and Carmen both had been psyched to leave, to have an adventure. They’d been to the city a few times, but their Dad hadn’t ever let them off the boat to wander. Well, Dad couldn’t do that anymore. Goodbye father. Hypothermic, fell off a cliff while bow hunting. The kids had found him, blue, sprawled in the wet snow, one arm twisted and his head bleeding. Before he passed he said to Joe, “Take care of your sister. Don’t count on your mom.”

“I’ll be the one taking care of you,” Carmen said to Joe as they carried their father’s body a few miles home. “‘I’m older.”

It had been a hungry spring without their father, and Joe worried about providing for Carmen and their mother. He felt too young. No one to help. Within two months of their father’s death their mother met another man. She said she needed someone to take care of her, and after that didn’t have much time for her kids -- this guy already had his own to feed. He said Joe and Carmen were old enough to fend for themselves.

“I have to do this, kids,” their mother said. “I have no choice.”

So Joe and Carmen loaded up the grain from the previous season, along with the spring harvest, just as their father would have done, and sailed down to the city, using the skills he’d taught them over the years. Today was the first time Joe had been off the boat in the city on his own.

He held the stone tightly. He would do anything to protect his sister. There’d been years when she was the only one he could talk to. There just weren’t that many other kids where they lived.

They decided they would have a look around the city, drumming up business before unloading their cargo, sacks of grain – wheat, dried corn, oats, barley – that they’d trade for goods the city people could still scavenge, like cigarettes, makeup, cans of food. Upstate, most of that stuff was gone. But in the city the high rises were endless larders full of stuff from the past, cans and bags and boxes of food. Joe loved the refried beans with the little cactus wearing a cowboy hat on the label. He would snag some of those.

It looked like there had been a flood recently, with a dark watermark running along the storefronts about three feet up. The tides down here at the mouth of the river were brutal, and with the flooding it was no wonder the city had emptied out. Still, everything looked shiny and glassy, unlike anything you’d see upstate, which was just forests and scrabbly little farms, nothing to look at, really. The city was something else, just seemed to go on forever. Joe thought he might get used to it.

They passed a row of old art galleries, glass fronts with nonsense paintings on the walls. As they walked, all they heard was the sound of their boots on the wooden walkways built over the water where the sidewalks used to be, and the quick flap of pigeon wings in and out of the buildings. The galleries were kind of cool, if weird. One had dusty photographs of high, snow-covered mountains with little fluorescent mountain climbers painted right on the photos. Another was a big empty room with a brightly painted statue of a guy wearing gold chains and a black cap, arms wrapped across his own chest.

They walked in and had a closer look. Red walls, gold floor, leaves that had blown in through an open window scattered here and there. A coffee cup rested on a desk in a little office next to a mound of raccoon pellets. On the wall behind was a huge painting of wild dogs.

“Can you imagine living here back then?” Carmen said wistfully. “The parties. The people all dressed up like in The Great Gatsby. Remember that book?”

“’So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past,” said Joe. “I’ll never forget the last line in that book.”

The boardwalk led up towards an abandoned mall, this giant thing of stairs. As they approached they heard something hard hit the boardwalk, and Joe jerked around to see what it was. A rock bounced into the water.

“Hey, you,” someone called to them.

“What the fu….?” Carmen said, looking up.

A pair of hands clutched the top edge of a panel truck, a face peeking over just enough to make out the forehead and nose. It was a girl and she looked scared, and possibly injured.

“Holy shit,” said Joe.

“I could use some help,” the girl called.

Joe looked at Carmen. Looked at the girl. Back at Carmen, who raised her eyebrows in a way that said, “Watch it.”

“What happened?” he called.

“I think I sprained my ankle. Maybe even broke it,” said the girl.

“On top of a truck?” he said.

“What were you doing up there?” said Carmen.

“I fell,” she said. “Last night, I think. I fell from up there on those ridiculous stairs”

Joe and Carmen gave each other a look like, WTF? and started figuring out how to get up there themselves, and then get her down.

On top of the truck, Sarah’s heart was pounding. She was nervous. She rarely saw strangers, let alone kids her age and definitely not this boy who was doing something to her insides. She had a crush. And she was in pain and stuck on the roof of a truck. She wasn’t sure how she was supposed to act. The poof, poof, boom from her heart went off inside her head like private fireworks. The boy from the boat. He was older, taller. It was not an easy feeling.

Who was the girl?

Sarah scooted herself to the other side of the truck where there was a steel ladder to the ground. No way she could climb down by herself.

“Over on this side,” she called down to the two of them. “Do you think you could help me over here?”

The kids hurried over and began to climb.

Chapter 4. The Route

My ankle was wrecked. I wasn’t gonna get down the ladder without help.

“I can’t walk,” I called to them.

The boy was the first one up the ladder. A wide smile.

Woah, I thought. That smile!

“What happened?” he said.

“I fell, last night. I feel so stupid.”

“What hurts?”

“My ankle hurts enough for five fucking ankles,” I said.

After a moment the girl peaked her head over the roof and said, ”This doesn’t look good. I’m Carmen. We’ll get you down.”

“You fell?” the boy said.

“Last night.”

“I’m Joe, by the way.”

He held out his hand, and my ankle screamed as I leaned forward to take it.

“Sorry,” he said. “I wasn’t thinking.”

Carmen helped from above and Joe from below as they bumped me down the ladder to the street. I actually cried out twice, and had to pull myself together when we reached the pavement. I put my arm around their necks and hopped along between them as we made our way to my house. Funny, but Joe and Carmen already felt like friends. It was a natural fit.

“This is weird,” said Joe as we hobbled past the old seminary, with it’s 19th century buildings and flowering vines and roses hanging over the iron fences. “Upstate you can watch the cows chew. Or you can throw rocks at a bottle. But I never saw a castle like this before. Amazing.”

“Can we sit for a second?” I said

I eased myself down onto some stone stairs steps.

“To me the city is kind of boring sometimes,” I said. “But I'm glad you like it.”

Carmen laughed.

“I guess it just depends on where you come from,” I said. “Me, I’m tired of the city. I want to see the world.”

“What do you mean?” Carmen asked.

“Well, the first thing I want to see is what’s on the other side.”

Carmen and Joe suddenly went quiet. Joe looked grave.

“What’s wrong?” I said. “What’d I say?”

“We were told never to talk about that,” Carmen said.

“Why?”

Carmen looked around to be sure no one was listening. Joe scanned the sky for drones. None. There never were.

“It’s dangerous. Those people are dangerous,” she said.

“Well I won’t tell if you don’t tell,” I said.

Joe smiled. It was as though a map appeared in front of me in that smile, like a layer over my vision, with a course marked in pencil that would lead me up the river past the Palisades and on through the woods and abandoned villages of that abandoned border territory, all the way to the wall that separated us from them. Me from my parents. The old ways from the new. I saw myself on that path. It was just a flash. But it was real all the same.

“They say that over there they hate us,” said Carmen.

“They think we started the whole virus. That’s why they built the wall,” said Joe. “And if we stay on this side, mind our own business, there won’t be a problem.”

“They’ve got all the things we used to have -- the lights, the computers -- you don’t want to mess with them cause then they’ll crush us,” Carmen said.

I’d heard this talk before. It seemed to comfort people to believe the other side was an unobtainable paradise. I couldn’t understand why.

“I’ve never seen anyone from over there, have you guys? I always hear how powerful they are, but I’ve never seen even one.”

“You don’t think you have -- you never know,” said Carmen.

I wondered what she meant by that.

“They’re sneaky,” she said.

“My parents are there,” I said. “My mom and dad.”

“Woah, really?”

“Why?” Joe said.

“It’s a crazy story, really. I don’t remember everything, but my Aunt and Uncle told me what happened. When I was a little kid my mom was really big on organizing people, like politics, you know? Before that the city was just like it is now -- everyone did their own thing. But my mom got the idea to organize. She thought our neighborhood, and then the city itself, could be a lot more powerful if everybody came together and chose a leader. She was going to be that leader. That was her plan. So she and my dad worked towards that, all the time. They got to know practically everyone who was around by name. My aunt says it was amazing. It was like the most successful thing that had happened in decades. Crazy. I don’t remember any of it cause I was too young,” I said.

“What happened?” Joe said.

“The Westerners over on the other side got scared. They didn’t want to have to deal with us. They were afraid we’d come and attack them and take their stuff -- and bring the virus. Or somehow politically we’d take over. They still believed we could infect them and ruin all they’d built up. So they sent a squad that kidnapped my parents right out of our house to put an end to the political organizing. And guess what? The city never tried to organize again. And I never saw my parents again.”

“Did you see them take your folks?”

“I guess I was sleeping. It was night. They took my parents away to the other side of the wall. When I woke up, my aunt and uncle were my only family. My parents were gone, and they never came back. Kidnapped. It’s been ten years, and I can barely remember them, no matter how hard I try.”

Chapter 5. Enter the Curandera

{I’m serializing my post dystopian novel here by posting one chapter a week. You can find the full archives here.}

I could see my aunt sweeping the sidewalk way up the block. She usually swept when she was nervous, and clearly that was the case now. I hated to upset her, but I also hated being around when she was upset. Her face twisted into a pretzel of fear, anger and relief when she saw me hobbling towards her, held up between the sibs.

“Oh my God! Sarah!” she cried out.

She hurried down the block to meet us.

“Where have you been?” she said. “I’ve been so freaked out.”

Her fearfulness irritated me. And that made me mad at myself – how could I be irritated with her? She was just worrying. That’s who she was.

I introduced Joe and Carmen and then sat on the nearest stoop to tell her the story.

“What on earth happened?”

“I fell off that ridiculous Schwarma and landed on the roof of a truck,” I said.

“What?”

“I’ll be ok. But I can’t put any weight on my ankle. And I’m dehydrated. And hungry. And tired. I couldn’t climb down, so I spent the night up there. Thank God these two happened by and rescued me. I'm sure I’d still be up there.”

“Thank you, thank you, thank you,” my aunt said, giving Joe and Carmen a hug.

“We were just walking by,” said Carmen.

“Oh my God, so lucky. You could have turned into a skeleton up there,” my aunt said. “Jesus! C’mon, let’s get you inside. When you didn’t come home we were afraid you’d run off.”

My aunt was always afraid she wasn’t good enough. That she hadn’t done enough for me. That she hadn’t been a good substitute for my own mother. And of course, no one could replace a mother, but she and my uncle had done the best they could. I loved them both, but they drove me nuts.

“I’d never run off without telling you,” I said.

But I knew, in fact, that I would.

I lay back on the sofa in the living room while auntie got us some sweet tea. With her, it was always the tea first, everything else later. She gave us each a cup and then had a good look at my ankle, which was swollen and bruised, with yellow and purple blotches and a red line radiating from the joint.

“This looks terrible,” she said. “Tell me if this hurts.”

She poked the swollen part and I gasped.

“Not good, not good at all.”

My uncle, who’d been napping upstairs, came in, his green eyes bright and sympathetic. He looked at my ankle and frowned.

“Not good,” he said. “Tara?”

“Yes, definitely,” my aunt said.

Tara was the healer we used whenever things took a turn for the worse, which, I’m glad to say, wasn’t often. I hadn’t seen her since the time a few years back when I’d had a leaky eye infection. For that, she took a dried mushroom out of a match box and and set it on the window sill and then blew the leftover dust from the matchbox into the corner of my eye. It stung like crazy but the next morning I woke up and there was no pus running down my cheek. I looked in the mirror, and it was clear.

My uncle ran off to get Tara, while Joe and Carmen and I drank tea and chatted to keep my mind off the pain.

“Where did you two come from?” my aunt asked.

“We’re from the boat from upstate, the grain boat that comes every year.”

“But I always buy from Joaquin.”

“That’s our father -- he passed.”

“Oh my goodness,” said my Aunt. “I’m so sorry to hear that.”

“He fell while hunting.”

“And your mother?”

“She’s with another man.”

My aunt shook her head in judgement. It was embarrassing.

“So you are left all alone. Just like this little one,” she said, patting my head. I shook her off and my ankle throbbed. I could feel it swelling. I winced as I reached for my tea.

“I’m sorry to upset you by talking about it, Sarah,” she said.

“Long ago,” I said. “And far away.”

I was drifting. I yawned.

I closed my eyes and glided on the pain into some kind of sleep.

I woke to Tara shaking my shoulders.

“Sarah, little Sarita,” she said in a singsong voice.

She had two vocal modes: deep and unnerving, the kind of low register voice that commanded you to pay attention; and high pitched and swirly, going up and down the register like a rollercoaster.

“What did you do to yourself, lady?” she said, her voice on the upward roll.

She wore a big muumuu almost the color of her skin. I could see dimples and stretch marks on her big calves as she bent close to my ankle.

“Problems here, girl,” she said. “I think it might be broken.”

Tara started giving orders: she needed a candle, a cup of rose petals, a shot glass of gin. She needed a blanket – “something you’d use on a picnic, so it can get dirty” – some cigarettes, some incense and a spoon.

My aunt and uncle immediately started searching.

“I’ve got some cigarettes,” I said.

My aunt looked surprised.

“Don’t worry. I just smoke them once in a while,” I said. “In that old Volvo down the street. I like to pretend I’m driving somewhere.”

My aunt blanched at my rebelliousness.

“Joe, can you grab them??” I said. “They’re in the dusty blue Volvo in front of number 389. Out the front door and to the right.”

Joe went out for the smokes.

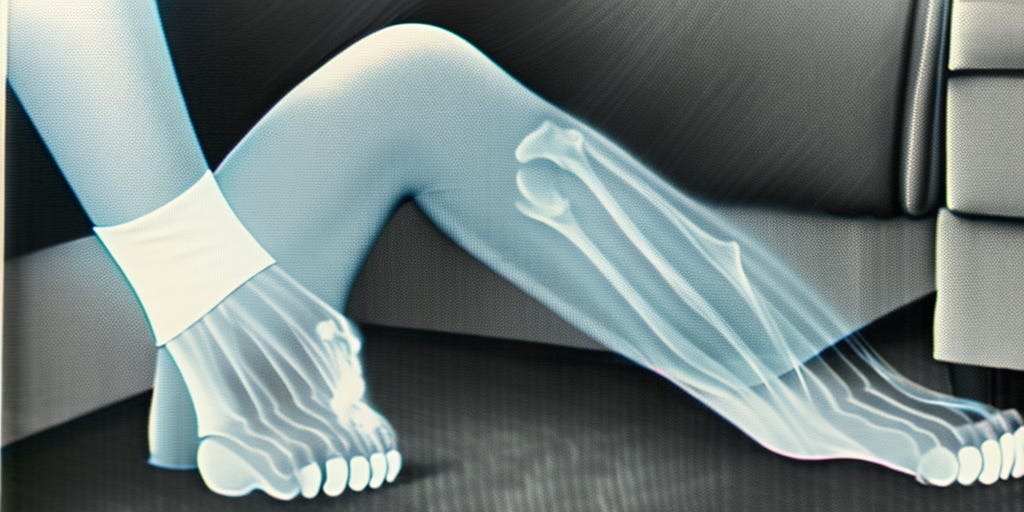

“I’m going to do an x-ray of your ankle,” Tara said.

“What?”

“I’m going to look inside your ankle and see if it’s broken,” she said.

I had no idea what she was talking about, but that didn’t much matter, because I trusted Tara to do the right thing.

She told me to just lie back and relax, close my eyes and try to let the pain be itself, rather than fighting it.

“Soon, honey, we’ll get this figured out,” she said.

Tara was the most important healer we had. She’d cured infections, reset bones, and even delivered difficult babies, the ones who didn’t really want to come into this world. This being New York, she didn’t charge for what she did. Almost nobody did. Everything was done either for yourself --- like growing a garden or fixing up your home -- or as a labor of love. We’d give her food whenever we had it, but that was about it. We didn’t have much of anything else to offer.

Joe showed up pretty quickly with the cigarettes, and it only took my uncle about an hour to gather everything that he’d gone searching for. When it was all together, Tara told everyone to leave the room.

“We’ll let you sleep,” Carmen said.

“Yeah, we should get back to the boat,” Joe said. We’ll come by to check on you tomorrow. We’ll bring you some millet.”

Oh, so he is a charmer, I thought, my eyes closed in pain. I tried to rise up off the couch to see them out, but Tara gave me a long sideways look, laughed, and said, “Everybody but you!”

What was I thinking?

“Normally I’d have you stand, but since your ankle is killing you, I’ll have to sit down next to you.”

Everything hurt like hell, my entire body, but especially my ankle. It was a throbbing pain that seemed to fall from my kneecap straight down into my ankle joint, where it collected in a big fat lump of hurt. The pain was something other than me. I wanted to kill it.

Tara lit a bundle of incense that sent deep grey smoke into the room. She set the sticks on the fireplace mantel and removed two smooth stones from her giant black leather bag. One was a shiny green, the other was grey and rough, like she’d dug it up at a farm. I winced as she brought the stones to the edge of my foot, right below the swollen ankle. I was afraid they’d hurt.

“Don’t touch me, please,” I said.

“What was that, honey?” she said as she set the stones against my swollen skin.

I smiled, almost chuckling. She’d tricked me, but the cool surfaces soothed me.

She stood and reached her arms towards the ceiling and recited an incantation, eyes back in her head. I think it was Cuban, but I couldn’t say for sure. As she spoke her arms went up and down, and her feet moved back and forth in rhythm to her voice. The incense filled my senses and suddenly she dropped her hands to my face and said,

“Whooooooosh.”

She pulled them quickly away.

Then again, right down on my face.

“Whooooooosh.”

Again and again she did it and my mind got foggy and pretty soon I was in a trance. Within this trance I felt enveloped by gray matter, like I was inside an infinite tweed jacket, snuggled and warm and protected, and definitely fuzzy. Strangely easy – not comforting, but just easy. I had no sense of the outside world. No sense of anything other than a humming, buzzing noise and the feeling of being encased. And a figure at the edges, moving carefully, acknowledging me. I didn’t think about it at the time, only after I came to. I felt a rushing sound, like I was traveling to the furthest reaches. I rushed and rushed and then just disappeared.

Later, the light through the windows entered my eyes. I could see the sun had changed. Morning was now afternoon.

I felt rested. I felt safe. I felt warm.

Tara sat near me, calves crossed under her thighs.

“I did a deep dive,” she said.

“That’s the X-ray?” I asked.

“I took a good look at the inside of your ankle, and nothing is broken. But you sure messed it up! I worked with it, energetically, I put energy into it, took old energy out.

The huge throbbing pain had subsided, which was pretty awesome.

“You’re going to be fine,” she said. “Just perfectly fine. But it will happen again unless you make some connections, energetically.”

“What do you mean?”

“I mean that I see you are fragile in some ways and the reason is you’ve lost – or are losing – the connection to your mother.”

“Not much I can do about that,” I said.

“Oh yes, yes there is…there is much you can do. You just have to wish for it. Wish for that closeness, that bond. It can come in many ways, darling. I will help you.”

“Ha,” I said, not meaning to really laugh. More out of surprise.

“Oh don’t worry, you don’t have to do nothing now. This is a long-term project! Anyway, it’s more about the search than the resolution.”

I looked down at my ankle, which she’d wrapped with some kind of leaf.

“There’s a poultice under there,” she said. “Leave it on until morning, and then take a bath and go on with your day. It will have totally healed by the end of the week.”

“Thank you, Tara,” I said.

“Blessings to you,” she said.

She gathered her things into her satchel. Then she sat again and just looked into my eyes. With anyone else it would have been unnerving. But with Tara it felt just right.

“You must be careful on this journey you are planning,” she said.

Holy shit, I thought.

“Who told you I was planning something?”

“You told me – your essence told me.”

“Wow,” I said. “I’ll be careful.”

She handed me a piece of paper.

“Use this if you need any kind of help,” she said.

On the paper were the words:

La Gloriosa Frieda

The Heights of Mantchuken

“The Heights is a village near the wall,” Tara said. “And La Gloriosa is an old friend of mine. Don’t hesitate to ask for her help if you need it. And don’t ignore her advice if she offers it.”

She headed for the door.

“I won’t get up,” I said.

She laughed, a good belly laugh.

“Tomorrow you will,” she said, and closed the door. “And your ankle will be completely fine in just a couple of days.”

Cool, I thought. I will take Joe and Carmen on a hunting trip to Central Park as soon as I’m better. I wanted to show them around, to thank them for rescuing me.

Not long after Tara left, my aunt came in and sat too close to me on the couch. She had a pained look, the look she got when things weren’t going her way -- which, honestly, was a lot of the time.

“I heard what you said to Tara about going on a journey,” she said.

“What?”

“I know you want to find your mom, but that’s — you don’t know what you’d be getting yourself into,” my aunt said.

“Well, first of all, I didn’t bring that up — Tara said she “felt it” or whatever during the x-ray. And second, while I appreciate all you do for me, it’s not really up to you if I decide to take a journey. I’m 16 now. I can take care of myself.”

Uncle Jessie appeared, trying to look casual by leaning against the doorway.

“I agree completely,” said Uncle. “You know, Famous Ray says children are adults by the time they are twelve.”

Famous Ray -- Jeez. He was this preacher they’d been following for the last few years. It was getting worse. They’d fallen under this guy’s spell. He wore spangled jumpsuits, big octagonal sunglasses, and a floppy hat, shiny things to distract you from the junk he pushed. It seemed that everyone in this city was enthralled by spiritualists, charlatans and prevaricators. But Famous Ray was the worst.

“By the time they are twelve?” I said. “That sounds a little creepy.”

My uncle sat in his chair, looking wounded.

“He doesn’t mean it like that. Always twisting things around -- why do you do that.”

“Jessie, am I right?” my aunt said. “Sarah can’t go to the other side. It’s forbidden. God knows what could happen. Right? Am I right?”

“After all we’ve done for you, you want to go and worry your aunt like this?” said my uncle.

“Oh my God. This has nothing to do with you, or with her.”

“We made a promise to your parents that we’d take care of you if anything happened to them.”

“Which you’ve done,” I said. “And I’m forever grateful. But I still don’t know what happened to my mom and dad. They just up and left. I don’t even remember what they looked like.”

“If anything good had happened they would have come back for you,” my uncle said.

“Jessie!” my aunt admonished him.

“Well, look at the situation here -- we’ve been raising Sarah since she was five years old and I think we have a right to tell her what’s what. No use protecting her from the truth.”

“Which is?” I said.

“The truth is that you’re not leaving for the wall and that’s that -- finito!” my uncle shouted, and walked out in the backyard.

“Sarah,” my aunt said, coming over to give me a hug.

I wanted no part of it. I got off the couch and hobbled out the front door and down the street to my Volvo to have a smoke.

No fucking way was I staying in New York forever without first figuring out what, and who, was out there on the frontier, where the Hard Fork began.

Chapter 6. Lunch on a Plaza at The Plaza

[Some days I write about aging, or the absurdities of life. Some days I serialize my dystopian/utopian novel, The Lost City of Desire. The previous chapters are archived here. I will release Chapter Seven next week.]

Joe, Carmen and I left early to have a good wander, planning to catch whatever we could that would be tasty. I had my compound bow and arrows, which were good for shooting animals from far away. Carmen carried a heavy hunting knife. She said she wasn’t much for killing, but she didn’t mind cutting them up once they were dead. Joe showed off his slingshot on the walk uptown, a piece of rubber tied to a small V-shaped branch. He’d scraped the bark off and the wood was pale blond and very smooth. Pretty, for sure.

“Why are you looking at me like that,” he said.

“Well, can you actually kill anything with that?”

He smiled.

“I mean, isn’t that what kids play with?”

He shrugged. I’d made him feel bad — by mistake. I wasn’t that good with people. I was a misfit -- I didn’t know what to say to them. I didn’t know how friends worked. We walked towards the pond at the lower end of Central Park.

“Does anybody claim this land?” Joe asked me.

“What do you mean?”

“Are they gonna kick us out if we hunt this pond?”

“Nah, first come first serve as far as I know,” I said.

“Back home clans will lay claim to something like this and you’ve got to get permission, or risk getting shot. Usually they want half of what you kill.”

I’d never heard that. No one had ever really taken control of the park --- or anything else around here, as far as I knew. The city was big enough for everyone, it seemed, there were so few of us.

“What’s that?” Carmen asked, pointing to a tall, slender tower that rose over 59th street.

“Apartments,” I said. “Crazy apartments.”

You had to stay clear of that block because windows kept falling out. I’d read that back in the day it had been the most expensive place to live in all of Manhattan -- funny that. The really fancy people all wanted to live on the top three or four floors. I’d considered walking to the top, but I never tried. About 90 stories, it is – that’s a lot of steps in the dark stairwell.

In the park the bright sun gave way to cool shade. The moss under my shoes was spongy and slick.

“What are we looking for here,” said Carmen.

“Doves, wild chickens, ducks…”

“Coons?”

“I never ate those, but sure, there are raccoons in here,” I said.

“No deer? Bear?”

“Nope.”

“Walruses?”

“Not since they closed the zoo,” I said.

I’d never seen the zoo when it was active, of course. I’d wandered through it a couple of times over the years, and had skateboarded the empty pool where the polar bears used to hang out. Some people worried that the white bears still lived in the park, but I didn’t — you had to avoid the pale grey skull and spine at the bottom of the empty pool as you skidded along the concrete.

“We’ve got pigeons and squirrels – those are the easiest to get, although the old timers say there aren’t as many pigeons as in the old days. There aren’t food scraps lying around, and the owls and falcons hunt them.”

“What about fox,” Joe said.

“Definitely a lot of them, but we don’t hunt them. It’s not our thing,” I said. “Too cute.”

I chuckled a bit at my earnestness, but I was dead serious all the same.

Carmen looked around, did a full 360, taking in the tall buildings on the park’s perimeter, the full oddness of this wilderness in the city.

Joe spotted the pond in the distance, brown water surrounded by tall grass. It was a meandering pond, with fingers extending here and there, and an island in the middle with a sun-worn sign reading: “No trespass. Bird sanctuary.”

“I wouldn’t mind some turtle,” said Joe.

“I never figured out how to catch them.”

“I’ll show you,” he said, smiling like he knew something I didn’t.

A few turtles relaxed on rocks in the sun about 30 feet up the shore. Joe motioned for Carmen and me to stop while he stood staring at the turtles. A massive snapper sprawled across one of the rocks, his neck craned up. Several smaller turtles sunned themselves nearby.

I knew people ate them, but how? The turtles wouldn’t let you sneak up on them – believe me, I’d tried. I mean, they looked good and I was always hungry for meat. Never felt crazy hungry, but I’d try to get anything I could to eat, whenever. Still, the one time I’d tried shooting a turtle the arrow bounced off the shell and disappeared into the water. I couldn't afford to lose arrows.

“You’ll never get one,” I said, as Joe edged closer to the pond.

He turned and put his finger to his lips for me to be quiet. Carmen and I stopped where we were and watched him crouch down and inch forward in the grass. The big turtle raised his head, and Joe froze. When the turtle relaxed its vigilance Joe reached back and pulled the slingshot out of his back pocket. He put a stone in the fold of the rubber band, pulled it back and let loose with a whoosh that took the turtle’s head right off. Even without a head its legs kept moving and it slid off the rock into the water.

“Holy shit,” I said.

The other turtles slid into the pond as Joe hopped from rock to rock until he could reach the big turtle. He pulled it out of the water and tied off the neck to keep the blood in and brought it back to shore, heavy as hell. He tied the animal to his back to butcher later -- weird how handsome he looked carrying that thing around.

It was an easy day of hunting. Over the next hour I got nearly a dozen ducks. Not that they were that brilliant at getting out of the way of my arrow. I think they got so much to eat in the summer that they were in a fat coma, just wanting to sleep as they floated around on the water. You probably could have just walked up and asked them to come home with you and nest in the fire pit, really. The hardest part was getting the dead ones out of the water before they floated away. This was when a dog would be nice, except for the rabies.

“You’re good,” Carmen said.

“We all gotta eat.”

We found a spot with some clear water and Carmen took her knife to the turtle while I worked on the ducks. Joe wandered off to find greens and wild garlic and soon we had the makings of a pretty great meal. There were guts in a pile, and the flies were buzzing, so we headed up the hill to 59th Street. This was one of those intersections that had collapsed when the water invaded from the flooded subway tunnels, the rotten water mains, from everywhere, but over the years someone had built a good bridge of planks across the arroyo.

“Fish down there?” Joe asked. “Bass?”

I didn’t know, I’d never thought about fishing the subways. Those tunnels were off limits. Too much mold, water and God knew what else.We landed on the square off the Plaza Hotel, where we built a fire in the shade of the statue of William Tecumseh Sherman, the gold leaf shiny in the sun. We rigged up some sticks and a metal grate to roast the ducks and the turtle and set everything to cook. The hot sun was nice. I’d never eaten turtle before, and it looked good! The weirdest stuff, really. Deep red meat with strangely iridescent green tinges in spots that made it seem even fresher. As it cooked, the legs were like spigots dripping fat to the embers which shot back with flame throwers that caramelized the ducks. I could feel the crisp skin in my mouth already.

Carmen put the turtle shell upside down close to the fire so it would dry into a serving bowl. I felt so hungry from all the walking, and the smell drove me mad.

“Smells like roasted chicken, right?” I said, and Joe and Carmen laughed. They were good hunters, stealthy. Bumpkins, we called them. Upstaters. I admired their skill. I pictured Joe’s muscles moving across his body in waves as he tiptoed towards the turtles until he was close enough to see their tongues move.

Cut into slices, the turtle cooked fast and we filled the shell with the fatty, roasted meat. I loved the burnt bits, which we ate as the ducks cooked on a spit.

“Do your Aunt and Uncle ever talk about what happened?” Joe asked me.

“Yeah, what the fuck did happen?” Carmen said. “I mean, obviously somebody lived in all the hotel rooms and apartments. Somebody shopped in Bergdorf Goodman and rode in all these dead cars.”

“They never have much to say about anything,” I said.

Their whole thing was about keeping things cool, peaceful, avoiding trouble, not making waves as they put it.

“I think it scared the shit out of them. After all, they were only kids when it all happened.”

“Same with our parents,” Joe said, and Carmen nodded.

The duck smelled almost sweet – the flame kissed the fat slicked skin. I was hungry again, even after all that roasted turtle.

“But I do know someone who’ll talk about it,” I said. “Someone who knows it all. I'm going to take you to him. His name is Terence.”

“That sounds great,” Carmen said.

“He’s like my second father.”

We ate our fill and then some.

“So they’re alive?” asked Carmen, lounging back against the statue’s base.

“My parents?”

I’d never considered otherwise. The question was shocking.

“I guess so,” I said. “I mean I assume so.”

“But you’ve never heard from them.”

“No.”

“Not once?”

I shook my head. “Wow,” said Joe. “Do you ever think about going to look for them?”

“You can’t,” said Carmen. “They wouldn’t ever let across the wall. You idyot.”

“I think about it every day,” I said.

And that was the truth. I’d had so many plans for going to find them. But I’d never done it. I’d never felt old enough, or strong enough – until now. Now, my belly full of meat, I was definitely going to do it.

I really like your illustrations!